Onibaba (1964) is a highly symbolic and progressive Japanese horror film which was way ahead of its time. Although it is in black and white, it is easy to forget about that as the story unfolds and the viewer is drawn in. Set in 14th century Japan, Onibaba delves into the struggle between the peasant and the samurai classes. The peasants dominate here as two women resort to murdering wayward and injured samurai and trading their armor and swords for bags of millet in order to survive. Based on a Buddhist story which is said to encourage women to be faithful, Onibaba undoubtedly turns the story on its end and gives the viewer a little insight into how far someone would go if the only other option was starving to death. I happen to think the story bears a striking resemblance to the Book of Ruth from the Bible which is about a woman and her daughter-in-law who are left alone much like these characters in Onibaba but survive in more respectable and acceptable ways.

Writer/director Kaneto Shindo said in an interview a few years back: “People are both the devil and God and are truly mysterious.” With the horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki still fresh in the minds of the Japanese (having only happened some 20 years before) certain scenes in Onibaba are said to symbolize the injuries and side effects so many of the Japanese sustained during the bombings.

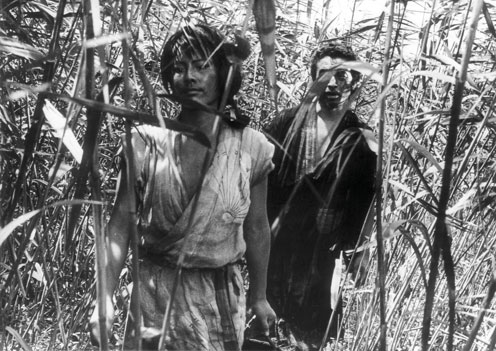

The film has a relatively small cast which helps to underscore the overpowering effect of the suzuki fields where the story takes place. The tall blades of grass serve as camouflage for the women and sets up a maze of sorts in which lost samurai venture into but never come out again.

An old well called “the hole” has no markings or warning signs and the women use it to dump the bodies. It sits gaping open, just a pit in the earth like some back door to hell. The hole reminds the audience that something bigger is at work here, that the tall grass is like a mote guarding some unseen castle, and the women are like watch dogs, dutifully serving their will to surivive. Nudity is presented as something natural rather than sexual as the women are frequently found in various stages of undress either while sleeping or just walking around. Then there’s the symbolism of the mask (which is introduced about 3/4 of the way through) that reminds me of that tale about the man who frowned all the time who was forced to wear a mask that had a smile. When they eventually took the mask off, his face had conformed to the mask and now had a permanent smile. This story is a little different, though.

The performances are raw and believable. The old woman, played by the director’s muse/wife Nobuko Otowa, is like an old witch from fairy tales the way she marches around the grass, eyes darting off in different directions, her frayed hair with the one white streak poking out about her head like writhing snakes.

Her daughter-in-law, played by Jitsuko Yoshimura, is dutiful but hungry, not just for food but for a little something else which she finds in their sleazy neighbor Hachi. To some, finding a man amidst all this loss might seem a cause for celebration (it was in the Book of Ruth), however, in Onibaba it serves as a catalyst that threatens the only stability these women have been able to find since they lost their son and husband, if having to kill to survive can even be considered something stable.

I found myself mesmerized by the performances, the cinematography and particularly the score which is a haunting and frenzied combination of taiko drums and insect noises. I definitely recommend this film. I found it to be a fascinating look into a time and place where no one can be trusted, an insane world which any one of us could face at any time if things ever get that bad. Rating: B+

[Source: Criterion]